Those Dam(n) Dams

Monday, Aug 13, 2007Elwha and Glines Canyon Dams

Olympic National Park, WA

After Vance received a response from the ‘Restore Hetch Hetchy’ organization about his “Vance’s Viewpoint’ on the Hetch Hetchy Dam in Yosemite National Park, we were quite intrigued by the existence of two dams located in Olympic National Park. How, after the Hetch Hetchy controversy did they get there, and were the rumors true that they were slated for removal? We went in search of the two dams in order to satisfy our curiosity about the how, why and when of dam removals.

What we learned was that both the Elwah and Glines Canyon Dams were constructed before Olympic National Park existed. The dams have been long opposed by the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, who saw their salmon fishery largely destroyed by the dams. As the dams aged and the calls for their removal increased, the National Park Service purchased both dams. Planning for the removal of the dams began, with the actual demolition process scheduled to start in 2008. The goal is the restoration of the entire Elwha River watershed as a fishery.

What we learned was that both the Elwah and Glines Canyon Dams were constructed before Olympic National Park existed. The dams have been long opposed by the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, who saw their salmon fishery largely destroyed by the dams. As the dams aged and the calls for their removal increased, the National Park Service purchased both dams. Planning for the removal of the dams began, with the actual demolition process scheduled to start in 2008. The goal is the restoration of the entire Elwha River watershed as a fishery.The removal of dams is more than just a passing fancy of ours. Back home in Western North Carolina, Duke Energy is undergoing the relicensing process for several of the hydroelectric dams near where we live. The power companies are provided usage of public waterways without any real costs other than the initial property purchases for the lakes. Part of the licensing process is to ensure that there is some form of ‘public mitigation’ for the ongoing right to use the water. In theory at least, this is supposed to compensate the public for the fact that ‘their’ waterways are being used by power companies to generate electricity for profit. In many cases, mitigation may take the form of campgrounds, boat ramps, etc….

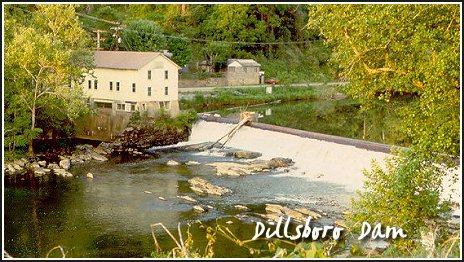

With the licensing cycle rolling around for multiple dams, the ‘mitigation’ negotiations can be interesting, particularly with environmental concerns receiving far more consideration than when these dams were built. Tradeoffs are typical, for example, the power companies may agree to increased waterflows down one river channel in order to avoid having to make major changes on another. In a novel twist, Duke Power is proposing to remove the small and aging Dillsboro Dam on the Tuckaseegee River as part of it’s mitigation for relicensing other dams in the area.

While this would seem to be a win-win all around, the devil is in the details. We belong to WATR, the Watershed Association of the Tuckaseegee River, which is the primary environmental ‘steward’ for the Tuckaseegee watershed. Although you would at first blush expect WATR to be in complete favor of the dam removal, it has taken no official position. The reason for this is concern over the large amount of sediment that would be released with the breaching of the dam. Because of the silt issue, from WATR’s perspective you are damned if you do, dammed if you don’t (pun intended!). Other groups wish to preserve the dam for its historic and scenic value. In either case, it has been a long running controversy back home.

While this would seem to be a win-win all around, the devil is in the details. We belong to WATR, the Watershed Association of the Tuckaseegee River, which is the primary environmental ‘steward’ for the Tuckaseegee watershed. Although you would at first blush expect WATR to be in complete favor of the dam removal, it has taken no official position. The reason for this is concern over the large amount of sediment that would be released with the breaching of the dam. Because of the silt issue, from WATR’s perspective you are damned if you do, dammed if you don’t (pun intended!). Other groups wish to preserve the dam for its historic and scenic value. In either case, it has been a long running controversy back home.Back up here in Washington State, the process for removing the dams is progressing a little smoother, if not a whole lot faster. The National Park Service purchased the dams from the previous owners, adding the lakes to Olympic National Park. Environmental Impact Statements, approvals, demolition project plans, etc…are pretty well taken care of. Now it is a matter of finalizing the funding to proceed with the removals, and replacement of existing infrastructure. For example, the municipal water source for Port Angeles is provided by the lake behind the Elwha Dam, and new intakes must be constructed for the city prior to the dam removal.

The primary motivation for the removal of the Elwha and Glines Canyon dams is to restore the Salmon runs on the Elwha River. The Elwha Dam sits a mere two miles inland from the ocean, and by all accounts it destroyed a tremendous salmon spawning run when constructed. Removing both dams will restore the Elwha, a glacier fed river that starts high in the Olympic Mountain Range, to its natural state. A worthy goal, indeed.

The primary motivation for the removal of the Elwha and Glines Canyon dams is to restore the Salmon runs on the Elwha River. The Elwha Dam sits a mere two miles inland from the ocean, and by all accounts it destroyed a tremendous salmon spawning run when constructed. Removing both dams will restore the Elwha, a glacier fed river that starts high in the Olympic Mountain Range, to its natural state. A worthy goal, indeed.The process for the removal of the Elwha river dams and the Dillsboro dams is much the same. The difference lies in how close the Elwha dams are to the ocean. Silt flushed out from the breaching of the dams is expected to help replenish several natural sand spits, also helping out the river delta, home to oyster and clam beds.

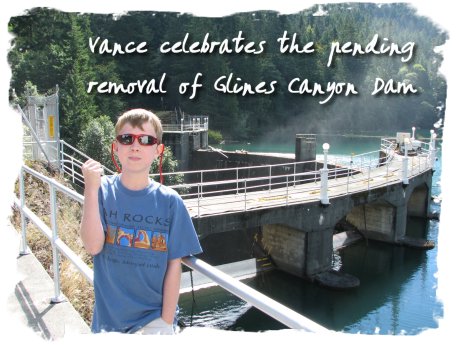

We found the Glines Canyon Dam first, after a lovely drive up the Elwha River. It’s an older dam in a small, narrow canyon. After looking around a taking a few pictures, we drove back down the Elwha towards the coast, stopping to ask directions to the Elwha River Dam at a really cute Ranger Station. There was an older couple from Virginia manning the station as volunteers – we had a great conversation with them. Like us, they were living in their camper for the season, volunteering at the Ranger Station because it would be closed otherwise due to lack of staffing at the park.

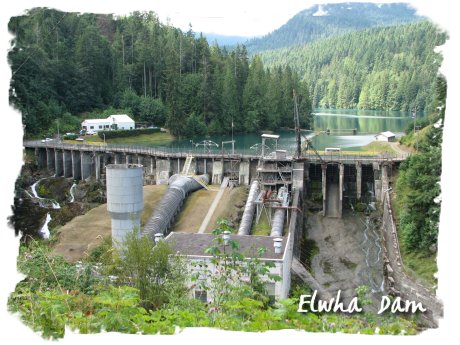

We found the Glines Canyon Dam first, after a lovely drive up the Elwha River. It’s an older dam in a small, narrow canyon. After looking around a taking a few pictures, we drove back down the Elwha towards the coast, stopping to ask directions to the Elwha River Dam at a really cute Ranger Station. There was an older couple from Virginia manning the station as volunteers – we had a great conversation with them. Like us, they were living in their camper for the season, volunteering at the Ranger Station because it would be closed otherwise due to lack of staffing at the park.Armed with directions, we finally found the Elwha Dam. This is beyond a doubt the ugliest dam I’ve ever laid eyes on! The picture below doesn't even come close to showing just how ugly the structure is. It looks like something slapped together with whatever materials happened to be on hand at the time, which might not be far from the truth. The dam was constructed in 1913 to provide electricity for a local mill, and by modern day standards, the amount of electricity it generates is minuscule. Hence, the widespread consensus for removal.

Improving Salmon habitat is a big issue these days in the Northwest. The damming of almost every river in the northwest, particularly the Columbia, has seriously reduced the Salmon runs to a fraction of their historical levels. Other than simply the economic impact of reduced fisheries, the role the salmon play in the overall ecosystem is slowly being recognized. According to one of the ranger programs we attended at Olympic, scientists are now demonstrating that spawning salmon play an important part in providing nitrogen fertilization in the soils.

How does this happen? Bears and other animals (eagles, for example) eat the salmon as they come in to spawn. The bear digests the salmon, then goes and poops in the woods. Salmon loaded poop provides lots of nitrogen for the soil (think fish emulsion). Research is indicating that the impact of this process has been severely underestimated. Much of the Puget Sound area is built on volcanic caused mud and ash flows (we’ll talk about this more later when we get to Mt St. Helens), and this nitrogen scattering process is an important way to start the initial fertilization process.

How does this happen? Bears and other animals (eagles, for example) eat the salmon as they come in to spawn. The bear digests the salmon, then goes and poops in the woods. Salmon loaded poop provides lots of nitrogen for the soil (think fish emulsion). Research is indicating that the impact of this process has been severely underestimated. Much of the Puget Sound area is built on volcanic caused mud and ash flows (we’ll talk about this more later when we get to Mt St. Helens), and this nitrogen scattering process is an important way to start the initial fertilization process.Learning about the two dams slated for removal was a nice counterbalance for Vance after his Hetch Hetchy experience, and provided some context for the controversy back home around the Dillsboro Dam. In general, as many of our nation's dams age, removal will become the only option as their structural integrity begins to diminish. While the dams under consideration for removal today tend to be minor structures, the experience gained should prove valuable down the road when addressing larger structures and lakes.

Vance: It’s great that these dams are slated for removal for a natural cause. People don’t have the right to just go and take something that isn’t theirs. The salmon deserve to have the spawning grounds restored. No parks should have any dams at all for people’s greed.

Destroying these two hideous structures of a dam will restore the

LIKE I SAID ON HETCH HETCHY, SEE WHAT YOU THINK AND MAKE AN OPINION! I’M COUNTING ON ALL OF YOU!!

| Previous - Bright ideas in the fog! | | Home | Index | | It's all about the Lakes! - Next |

<< Home